All the bound protons and neutrons in an atom make up a tiny atomic nucleus, and are collectively called nucleons. The radius of a nucleus is approximately equal to ![\begin{smallmatrix}1.07 \sqrt[3]{A}\end{smallmatrix}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/7/0/d/70dc2ced9f84c7b142a9e1105af95744.png) fm, where A is the total number of nucleons.[51] This is much smaller than the radius of the atom, which is on the order of 105 fm. The nucleons are bound together by a short-ranged attractive potential called the residual strong force. At distances smaller than 2.5 fm this force is much more powerful than the electrostatic force that causes positively charged protons to repel each other.[52]

fm, where A is the total number of nucleons.[51] This is much smaller than the radius of the atom, which is on the order of 105 fm. The nucleons are bound together by a short-ranged attractive potential called the residual strong force. At distances smaller than 2.5 fm this force is much more powerful than the electrostatic force that causes positively charged protons to repel each other.[52]

Atoms of the same element have the same number of protons, called the atomic number. Within a single element, the number of neutrons may vary, determining the isotope of that element. The total number of protons and neutrons determine the nuclide. The number of neutrons relative to the protons determines the stability of the nucleus, with certain isotopes undergoing radioactive decay.[53]

The neutron and the proton are different types of fermions. The Pauli exclusion principle is a quantum mechanical effect that prohibits identical fermions, such as multiple protons, from occupying the same quantum physical state at the same time. Thus every proton in the nucleus must occupy a different state, with its own energy level, and the same rule applies to all of the neutrons. This prohibition does not apply to a proton and neutron occupying the same quantum state.[54]

For atoms with low atomic numbers, a nucleus that has a different number of protons than neutrons can potentially drop to a lower energy state through a radioactive decay that causes the number of protons and neutrons to more closely match. As a result, atoms with roughly matching numbers of protons and neutrons are more stable against decay. However, with increasing atomic number, the mutual repulsion of the protons requires an increasing proportion of neutrons to maintain the stability of the nucleus, which modifies this trend. Thus, there are no stable nuclei with equal proton and neutron numbers above atomic number Z = 20 (calcium); and as Z increases toward the heaviest nuclei, the ratio of neutrons per proton required for stability increases to about 1.5.[54]

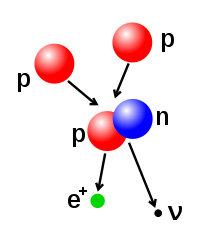

The number of protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus can be modified, although this can require very high energies because of the strong force. Nuclear fusion occurs when multiple atomic particles join to form a heavier nucleus, such as through the energetic collision of two nuclei. For example, at the core of the Sun protons require energies of 3–10 keV to overcome their mutual repulsion—the coulomb barrier—and fuse together into a single nucleus.[55] Nuclear fission is the opposite process, causing a nucleus to split into two smaller nuclei—usually through radioactive decay. The nucleus can also be modified through bombardment by high energy subatomic particles or photons. If this modifies the number of protons in a nucleus, the atom changes to a different chemical element.

If the mass of the nucleus following a fusion reaction is less than the sum of the masses of the separate particles, then the difference between these two values may be emitted as a type of usable energy (such as a gamma ray, or the kinetic energy of a beta particle), as described by Albert Einstein's mass–energy equivalence formula, E = mc2, where m is the mass loss and c is the speed of light. This deficit is part of the binding energy of the new nucleus, and it is the non-recoverable loss of the energy which causes the fused particles to remain together in a state which require this energy to separate.

The fusion of two nuclei that create larger nuclei with lower atomic numbers than iron and nickel—a total nucleon number of about 60—is usually an exothermic process that releases more energy than is required to bring them together.[59] It is this energy-releasing process that makes nuclear fusion in stars a self-sustaining reaction. For heavier nuclei, the binding energy per nucleon in the nucleus begins to decrease. That means fusion processes producing nuclei that have atomic numbers higher than about 26, and atomic masses higher than about 60, is an endothermic process. These more massive nuclei can not undergo an energy-producing fusion reaction that can sustain the hydrostatic equilibrium of a star.

0 comments:

Post a Comment