In the previous section temperature was defined in terms of the Zeroth Law of thermodynamics. It is also possible to define temperature in terms of the second law of thermodynamics, which deals with entropy. Entropy is a measure of the disorder in a system. The second law states that any process will result in either no change or a net increase in the entropy of the universe. This can be understood in terms of probability. Consider a series of coin tosses. A perfectly ordered system would be one in which either every toss comes up heads or every toss comes up tails. This means that for a perfectly ordered set of coin tosses, there is only one set of toss outcomes possible: the set in which 100% of tosses came up the same.

On the other hand, there are multiple combinations that can result in disordered or mixed systems, where some fraction are heads and the rest tails. A disordered system can be 90% heads and 10% tails, or it could be 98% heads and 2% tails, et cetera. As the number of coin tosses increases, the number of possible combinations corresponding to imperfectly ordered systems increases. For a very large number of coin tosses, the combinations to ~50% heads and ~50% tails dominates and obtaining an outcome significantly different from 50/50 becomes extremely unlikely. Thus the system naturally progresses to a state of maximum disorder or entropy.

It has been previously stated that temperature controls the flow of heat between two systems and was just shown that the universe tends to progress so as to maximize entropy (this is expected of any natural system). Thus, it is expected that there is some relationship between temperature and entropy. To find this relationship, the relationship between heat, work and temperature is first considered. A heat engine is a device for converting heat into mechanical work and analysis of the Carnot heat engine provides the necessary relationships. The work from a heat engine corresponds to the difference between the heat put into the system at the high temperature, qH and the heat ejected at the low temperature, qC. The efficiency is the work divided by the heat put into the system or:

(2)

(2)

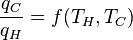

where wcy is the work done per cycle. The efficiency depends only on qC/qH. Because qC and qH correspond to heat transfer at the temperatures TC and TH, respectively, qC/qH should be some function of these temperatures:

(3)

(3)

Carnot's theorem states that all reversible engines operating between the same heat reservoirs are equally efficient. Thus, a heat engine operating between T1 and T3 must have the same efficiency as one consisting of two cycles, one between T1 and T2, and the second between T2 and T3. This can only be the case if:

Since the first function is independent of T2, this temperature must cancel on the right side, meaning f(T1,T3) is of the form g(T1)/g(T3) (i.e. f(T1,T3) = f(T1,T2)f(T2,T3) = g(T1)/g(T2)· g(T2)/g(T3) = g(T1)/g(T3)), where g is a function of a single temperature. A temperature scale can now be chosen with the property that:

(4)

(4)

Substituting Equation 4 back into Equation 2 gives a relationship for the efficiency in terms of temperature:

(5)

(5)

Notice that for TC = 0 K the efficiency is 100% and that efficiency becomes greater than 100% below 0 K. Since an efficiency greater than 100% violates the first law of thermodynamics, this implies that 0 K is the minimum possible temperature. In fact the lowest temperature ever obtained in a macroscopic system was 20 nK, which was achieved in 1995 at NIST. Subtracting the right hand side of Equation 5 from the middle portion and rearranging gives:

where the negative sign indicates heat ejected from the system. This relationship suggests the existence of a state function, S, defined by:

(6)

(6)

where the subscript indicates a reversible process. The change of this state function around any cycle is zero, as is necessary for any state function. This function corresponds to the entropy of the system, which was described previously. Rearranging Equation 6 gives a new definition for temperature in terms of entropy and heat:

(7)

(7)

For a system, where entropy S may be a function S(E) of its energy E, the temperature T is given by:

(8)

(8)

i.e. the reciprocal of the temperature is the rate of increase of entropy with respect to enDefinition by statistical mechanics

The argument in the previous section is how the relation between entropy and heat was arrived at historically. Modern definition of temperature is given in Statistical mechanics and it is defined in terms of the fundamental degrees of freedom of a system (see the article entropy for details). Eq.(8) of the previous section is then taken to be the defining relation of the temperature. Eq. (7) can be derived from the definition of entropy, see e.g. here.

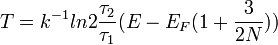

Generalized temperature from single particle statistics

It is possible to extend the definition of temperature even to systems made of few particles, like in a quantum dot. The generalized temperature is obtained by considering time ensembles instead of configuration space ensembles given in Statistical mechanics in the case of thermal and particle exchange between a small system of fermions (N even less than 10) with a single/double occupancy system. The finite quantum grand partition ensemble[5], obtained under the hypothesis of ergodicity and orthodicity, allows to express the generalized temperature from the ratio of the average time of occupation τ1 and τ2 of the single/double occupancy system [6]:

where EF is the Fermi energy which tends to the ordinary temperature when N goes to infinity.

0 comments:

Post a Comment